It has been around for nearly 190 years but the concept is three times older than that. Joseph Niepce, a failure at drawing, and his primary fascination of lithography didn’t pan out after his artist son was drafted to fight in the battle of Waterloo, he turned his attention to capturing images that he referred to as heliographs, Greek for “writing from the sun.” He is credited with shooting the first known image (shown here), a low-quality washed out picture difficult to decipher. It shows a building, with a tree to the left, and since the exposure lasted eight hours, the sun had a chance to shine on both sides of the building.

It has been around for nearly 190 years but the concept is three times older than that. Joseph Niepce, a failure at drawing, and his primary fascination of lithography didn’t pan out after his artist son was drafted to fight in the battle of Waterloo, he turned his attention to capturing images that he referred to as heliographs, Greek for “writing from the sun.” He is credited with shooting the first known image (shown here), a low-quality washed out picture difficult to decipher. It shows a building, with a tree to the left, and since the exposure lasted eight hours, the sun had a chance to shine on both sides of the building.This was in June or July 1827, after 12 years of research and experimentation. Excited with his results, Niepce moved from France to England to request the assistance of the Royal Society, which was then the leading authority for all things relating to science, but since they had a strict rule that they would not publicize any discovery that contained an undivulged secret, they turned him down. Dejected, he returned to France and met with Louis Daguerre in 1829, and in one of those unfortunate twists of fates, Niepce died four years later and never enjoyed the fame and popularity of his invention.

Daguerre took over the experimentations, developing new plates on which to capture images, reducing the exposure time down to a half-hour and discovered that the images could become permanent if they were immersed in salt.

Leading scholar and well respected historical painter Paul Delaroche was asked by the French government to head a committee to study the new Daguerreotypes. In his report, he declared, "from today, painting is dead!" which turned out to be a similar and mistaken comment that has been attributed to the development of the telephone, radio, television, Internet…each one supposedly leading to the demise of the former. In fact, an interesting side note is that one would expect the invention and proliferation of the cell phone to herald the end of the pay phone, but it is just the opposite as there are more pay phones in operation today than ever.

Photography today is taken for granted, easily enough with the advent of camera phones, digital camera, webcams, security cameras and hidden cameras. Photography is everywhere today, but back in the day where the concept of capturing a likeness of a person, scene or landscape without the use of paint, canvas or, above all, talent, was a remarkable sensation that swept the world as soon as the Daguerreotype was announced. In a book written by Marc Gaudin in 1844, he provides an eyewitness account of the excitement that followed the announcement of the Daguerreotype:

“The Palace...was stormed by a swarm of the curious at the memorable sitting on 19 August, 1839, where the process was at long last divulged. Although I came two hours beforehand, like many others I was barred from the hall (and) was...with the crowd for everything that happened outside. At one moment an excited man comes out; he is surrounded, he is questioned, and he answers with a know-it-all air, that bitumen of Judea and lavender oil is the secret. Questions are multiplied but as he knows nothing more, we are reduced to talking about bitumen of Judea and lavender oil. Soon a crowd surrounds a newcomer, more startled than the last. He tells us with no further comment that it is iodine and mercury... Finally, the sitting is over, the secret divulged... A few days later, opticians' shops were crowded with amateurs panting for daguerreotype apparatus, and everywhere cameras were trained on buildings. Everyone wanted to record the view from his window, and he was lucky who at first trial formed a silhouette of roof tops against the sky. He went into ecstasies over chimneys, counted over and over roof tiles and chimney bricks - in a word, the technique was so new that even the poorest plate gave him unspeakable joy...”

The Daguerreotype was not without competition, as is every new discovery. William Henry Fox Talbot, also a failure at drawing, turned to mechanical means of capturing images. After countless attempts, he developed a process that cut the exposure time to only a few minutes, and, by accident, created a new development process that used paper instead of metal and glass plates.

The earliest surviving paper negative is of the now famous Oriel window in the South Gallery at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire, where he lived. It is dated August 1835. Talbot's comments read, “When first made, the squares of glass about 200 in number could be counted, with help of a lens.” Quite annoyed that Daguerre was getting all the attention for something he felt he deserved credit for, he became pleasantly surprised to discover that his process was different than Daguerre’s and equally patented, which he did so on February 8, 1841. From this negative image, he was able to develop a positive paper image, the first to do so.

The earliest surviving paper negative is of the now famous Oriel window in the South Gallery at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire, where he lived. It is dated August 1835. Talbot's comments read, “When first made, the squares of glass about 200 in number could be counted, with help of a lens.” Quite annoyed that Daguerre was getting all the attention for something he felt he deserved credit for, he became pleasantly surprised to discover that his process was different than Daguerre’s and equally patented, which he did so on February 8, 1841. From this negative image, he was able to develop a positive paper image, the first to do so.The term “photograph” is credited to Sir John Frederick William Herschel, the only son of a distinguished British astronomer William Herschel, in a paper titled “Note on the art of Photography, or The Application of the Chemical Rays of Light to the Purpose of Pictorial Representation,” presented to the Royal Society on 14 March 1839. He also coined the terms "negative" and positive" in this context, and interesting enough also the pedestrian term “snap-shot.”

He became interested in photography after seeing the results of the Daguerreotype and was associates with both Daguerre and Fox Talbot, knowing first-hand the outcome of their experiments. Herschel took the first photograph on glass in 1839; it shows his father telescope in Slough, near London.

He became interested in photography after seeing the results of the Daguerreotype and was associates with both Daguerre and Fox Talbot, knowing first-hand the outcome of their experiments. Herschel took the first photograph on glass in 1839; it shows his father telescope in Slough, near London.The rest is history.

Like any new technology, taking a photograph was an expensive one-time adventure for many wealthy people. The process was complicated, time consuming and required a great deal of skill and talent to combine the right chemicals at the right times in order to produce any recognizable image. Soon the process was simplified, new equipment was developed and put into the hands of hordes of people.

One hundred and six years ago, the Brownie camera was introduced by Kodak, literally putting the first cameras into the hands of thousands of people. In 1898, George Eastman asked Frank Brownell, his camera designer, to design the least expensive camera possible while at the same time making it effective and reliable. Eastman realized that if the cost could be reduced that more people, especially children, might take up photography which would lead to future film sales. Brownell came up with the Brownie Camera which Kodak started selling in February 1900. “The Brownie” was named, not as a variation of Brownell’s name, but instead after the characters created by the Canadian author and illustrator Palmer Cox, a popular series of characters for children throughout the 1890s. By adopting the name and using the characters in advertising, Eastman gained a major marketing advantage, and the term “Brownie camera” has been synonymous with popular photography for the last 100 years, producing the line of cameras well into the 1960s.

Today, one would be hard pressed to find someone who doesn’t own a device that takes pictures of some kind, and the vast majority is certainly digital. But, technology may be the problem, as the digital camera may be the worst development of the photographic genre in the preservation of the world around us. It is temporary, transitory, everything paper photographs are not.

When is the last time you held a digital image in your hand? When was the last time you opened a photo album only to discover you pictures were corrupted? Yes, I have a digital camera and yes, I use it extensively to record everything about my life and the lives of my family… and sometimes I use it to capture the images of the dumbest things. The difference is that I print them out, creating a hardcopy paper evidence that we actually existed, unlike those that may have recorded their child’s third birthday on a Beta tape. How can you play it back?

There is something magical about a photograph, especially if you can get past the subject matter. If you can stripe away the emotion associated with the image—you baby or your long lost grandmother—and see it merely as a person in a picture, it becomes a time machine. It is one of the reasons that black and white photography carry with them an aura of artistic quality about it; the color isn’t there to get in the way of what is really important about the picture. If the picture is good enough and the photographer knows what he is doing, attention is immediately drawn to a specific point in the picture—the eyes, a smile, the focus of the image—and then the viewer is led through the photograph, which is where it really tells a story.

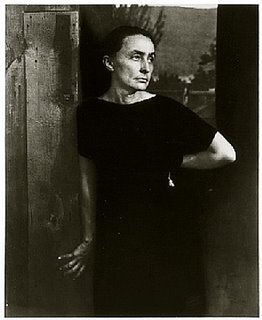

Take for example this portrait by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), one of the 20th Century’s most instrumental photographers in making photography an acceptable art form along side painting and sculpture. It helped that he took pictures that resembled the finer arts. In 1902, with camera clubs all the rage, he organized an invitation-only group dubbed the “Photo-Secession” with the main goal to elevate mere picture taking to an art form, “a distinctive medium of individual expression.” The elite group of shutterbugs, including Edward Steichen, Gertrude Kasebier, Clarence White and Alvin Langdon Coburn, published “Camera Work” a quarterly photographic journal.

Take for example this portrait by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), one of the 20th Century’s most instrumental photographers in making photography an acceptable art form along side painting and sculpture. It helped that he took pictures that resembled the finer arts. In 1902, with camera clubs all the rage, he organized an invitation-only group dubbed the “Photo-Secession” with the main goal to elevate mere picture taking to an art form, “a distinctive medium of individual expression.” The elite group of shutterbugs, including Edward Steichen, Gertrude Kasebier, Clarence White and Alvin Langdon Coburn, published “Camera Work” a quarterly photographic journal.When you look at this picture for the first time, what do you see? Eyes, right? As human beings, we strive for communication so it makes perfect sense that we look directly to the eyes first; it is a portrait photographer’s key to an emotional story within the picture. What’s next? Did you look at the mouth, maybe the nose? I saw the mouth and then my eyes dropped down to her elbow. Did yours? The three locations, the eyes, the mouth and the elbow are all related in emotion and those are the actual subjects of this picture. An akimbo elbow shows impatience, disappointment, disenchantment maybe? She looks as if some element of her life—or at least something in her field of vision—is disturbing. But wait, look at her other hand, the one grasping the fence. It looks strained, desperate to hold onto something tangible, solid and reassuring.

If this were in color and not black and white, all of these subtleties of light and dark, the one great contrast, would be lost. The fence would be brown, the trees and mountain behind her green and her skin probably a little off of pink, but there would be tones of color. All of the emotion would be lost. The subject would be an older woman standing by a fence in her backyard.

But it just isn’t the case, which is why this picture lends itself closer to art than just a regular snapshot you’d find in anyone’s scrapbook. But who is the woman in the picture? Ironically enough, the subject of this photograph is Stieglitz’s wife from 1924 until his death, a famous painter in her own right, Georgia O’Keeffe. Throughout their time together, he took hundreds of pictures of O’Keeffe (and later nude shots of heiress Dorothy Norman) and these photographs are often considered the first pictures to suggest that singular areas of the body have the potential to be considered art.

Do you see it now?

Photography can be haunting. Physically haunting in some cases, as in the case of the Chiapas Highland Mayans around the communities of San Cristobal de Las Casas, in Mexico, who are still afraid of cameras because they not only don’t like being exploited by random tourists and get nothing in return, but on a deeper level, they feel that when someone takes a picture of them, the impersonal exchange of the photographer is robbing them of their chu’lel, a complex Mayan concept of the “vital energy” or “life force,” something that all Highland Mayans share with other objects. It isn’t their soul a camera robs in question, in this case, but instead it is akin to someone walking into their house without knocking—an impersonal action the Mayans detest.

Take this photograph for example. What do you see? Again we look at the eyes first, but this time we see something darker, slightly haunting. Her puffy jowls pulls those eyes down and the shadows provide a deep sunken appearance. She dressed as Little Red Riding Hood with her basket in the forest on the way to her (by then dead and devoured by the wolf) grandmother’s house. The camera isn’t capturing her image as much as she is staring it down, demonically. Black and white… rather the absence of color, this time, doesn’t do the emotions of the image any favors. It darkens the red of her cloak, the blue of her dress and the green of the trees, whereas color would brighten this photograph tremendously. Believe it or not, but she’s a blonde… and just to give you a sense that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, this little girl’s uncle called this portrait of his niece “a gem.” And this little girl? Why she’s Agnes Grace Weld, poet Alfred Lord Tennyson’s niece (on his wife’s side), and the man behind the camera was none other than Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a man that represents everything exciting and beautiful about a child’s imagination… you may better know him as Lewis Carroll.

Take this photograph for example. What do you see? Again we look at the eyes first, but this time we see something darker, slightly haunting. Her puffy jowls pulls those eyes down and the shadows provide a deep sunken appearance. She dressed as Little Red Riding Hood with her basket in the forest on the way to her (by then dead and devoured by the wolf) grandmother’s house. The camera isn’t capturing her image as much as she is staring it down, demonically. Black and white… rather the absence of color, this time, doesn’t do the emotions of the image any favors. It darkens the red of her cloak, the blue of her dress and the green of the trees, whereas color would brighten this photograph tremendously. Believe it or not, but she’s a blonde… and just to give you a sense that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, this little girl’s uncle called this portrait of his niece “a gem.” And this little girl? Why she’s Agnes Grace Weld, poet Alfred Lord Tennyson’s niece (on his wife’s side), and the man behind the camera was none other than Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a man that represents everything exciting and beautiful about a child’s imagination… you may better know him as Lewis Carroll.Pictures like this one and millions of others are especially haunting because they show a person who is in all likelihood, dead. If you look at it like that, you are quite literally, looking back in time to a person’s life, something no painting could ever capture. There is no life in a painting, at least, an semblance of reality because a painting is only a facsimile of nature, regardless of how accurate the artists.

The next time you look at a picture of someone, a woman standing by a fence or a little girl playing dress up during story time, look beyond what your eyes actually see. You’re missing most of what the photographer was trying to tell you, but most importantly, remember that you would never have been able to even see that photo if someone didn’t preserve it all these years.

Get your digital images off of your computer, onto acid-free paper, and into a photo album. Protect that album as if you were protecting your future. After you’re long gone, they are all the remaining evidence that you ever existed. Do you want your life stored on an irretrievable hard drive of an antique computer that is resting at the bottom strata of the local dump for all eternity or maybe in a museum showing what it was like to be alive during your era of history?

. Perhaps the Mayan’s were onto something: Maybe your life force can be stolen by a camera. I know when I see a picture of an old ancestor in my family tree, I see a tiny bit of myself in that grainy black and white.

All of this from a photograph

No comments:

Post a Comment